When the Cloud Comes Home: Reflections from the Other Side of the Hype Cycle

“IT organizations are moving from an application base that is primarily non-virtualized to one that is largely cloud-based. It is critical to develop a unified strategy determining which applications are suited to SaaS, and both private and public mode model of IaaS. Infrastructure executives see cloud as the dominant technology trend today. Spending on cloud services is growing quickly and will soon become significant.”

These were the few opening lines of a landmark study that I participated in authoring back in 2011. It was a time when cloud was not a trend, it was a change in thinking. This was because at that time cloud promised speed, scale, and salvation. It was the answer to inefficiency, fragmentation, and spiraling IT infrastructure costs. All this and much more.

We saw the light. We believed in it. We drank Kool-Aid. We evangelized it. And, in many ways, we were not entirely wrong. But here I am more than a decade later, much wiser, much more greyed-out, much more skeptical, watching a curious reversal quietly unfolding—cloud repatriation.

Company after company, industry after industry, that once raced to the cloud as if their life depended on it are now pulling workloads back onto on-premise infrastructure or hybrid models. This is in no way a rejection, but it's surely a recalibration. The wheel is turning again.

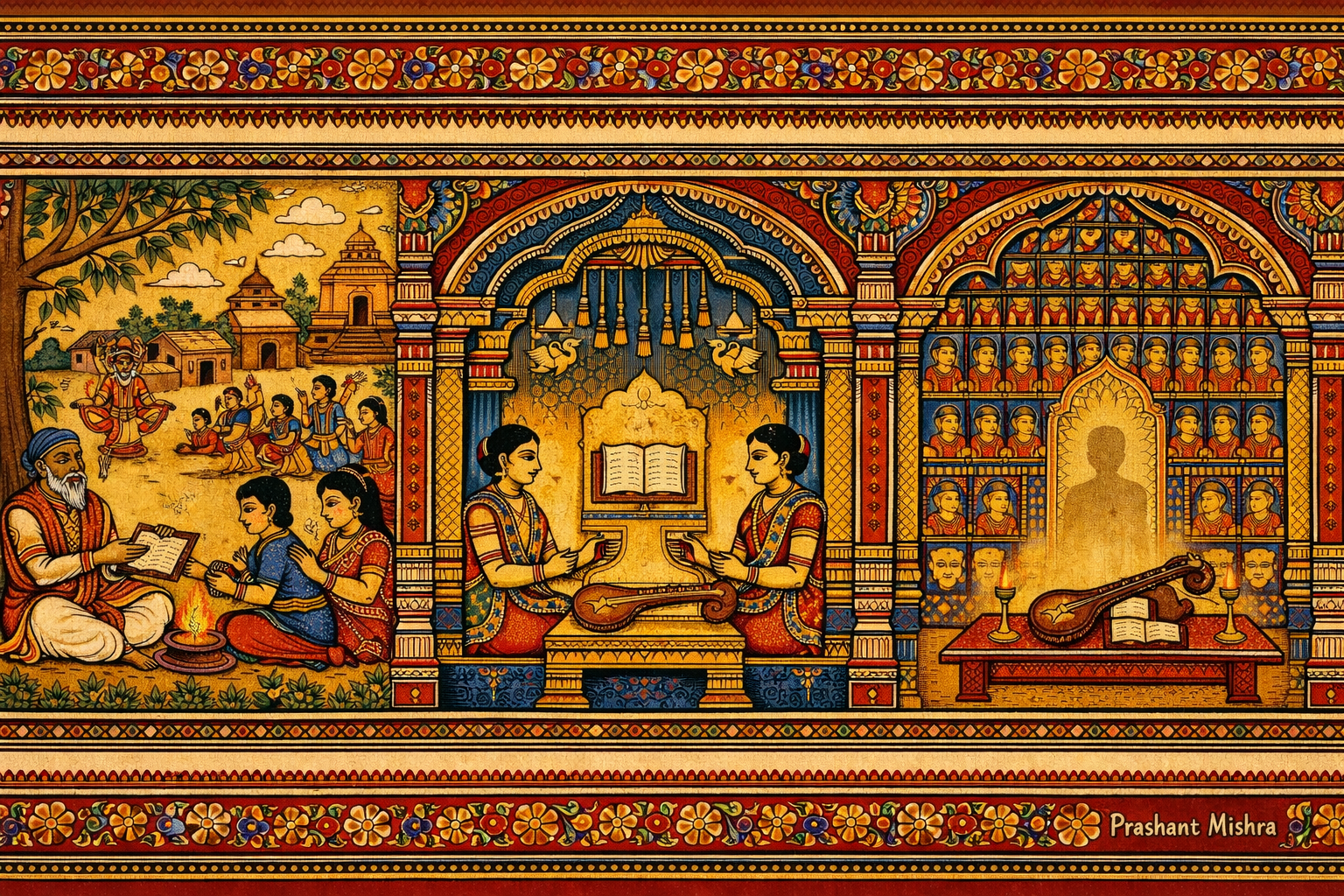

What I write today is more than a story; it is a meditation on cycles. A reflection on adoption and abandonment, enthusiasm and caution, and centralization and decentralization. It reminds us that in technology, as in life, there is no final arrival point but only Dharma, which is a dynamic balance, a mindful alignment, with what that particular moment truly demands.

The global financial crisis in 2008-2009 had left organizations reeling, and amongst other things, there was an immense pressure to optimize CAPEX. IT, traditionally categorized as a support function, was viewed as the proverbial white elephant; therefore, CFOs put incredible pressure to make IT budgets leaner. However, on the IT side, leaders faced an aging on-premise infrastructure, system silos, low utilization rates, and high maintenance costs. That was the inside story. Externally, companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook were rapidly transforming user expectations from what this user segment called “IT.” Employees and customers alike wanted the “digital experience,” “always-on IT,” and faster time-to-market for products and services. It was the era of the “consumerization of IT.” The financial crisis had also jolted organizations to hedge their bets by going aggressively global, leading to rampant globalization and a distributed workforce. All this had IT leaders on their tenterhooks. Enter cloud computing.

Software-as-a-Service was already showing tremendous promise with the rise of companies like Salesforce and Google pushing their now ubiquitous apps. Business leaders saw the cloud as the elegant solution. Cloud computing provided elastic compute, on-demand storage, and rapid provisioning across time zones and regions. The days of bureaucratic IT provisioning were done. The answer for everything plaguing IT seemed to lie in the cloud, and the message was clear: “adopt or die.” The promise was intoxicating—agility, innovation, and cost-efficiency on tap.

But just like everything else, the sales pitch is always much better than the delivery. What was not expected, anticipated, or appreciated at that time were the invisible trade-offs. Huge hidden costs lie buried in data egress fees. The network latency issues. And, finally, that smart smirking devil in the details of the service level agreements. Vendor lock-in became the name of the game. Going to the cloud was easy; moving out was the stuff that nightmares were made of. Control, performance tuning, and compliance, which were once in the hands of battle-hardened IT leaders, were now distributed, abstracted, and often completely opaque.

I am not saying that cloud adoption was wrong. My post is not against any company, technology, or trend. My post is about the cyclical nature of things. Cloud adoption was the right thing to do at that time given the constraints. It was a leap of faith in the world that craved newness and agility, but every leap comes with gravity. And that gravity is what is swinging the pendulum back today.

So here we are in a new age of the cloud journey called cloud repatriation, which is another fancy term for organizations moving data workloads or applications away from the cloud and back to either on-prem infrastructure or hybrid models. Many organizations are doing this, and there are many reasons for doing so. First and foremost, amongst them, is cost predictability. Cloud providers may have lower entry costs, but long-term operational costs can be unpredictable and unwieldy. The second reason is data sovereignty. Performance optimization is the third reason, as applications tend to perform better when coupled to infrastructure tightly tuned to them, which is only possible in a dedicated environment. And lastly, cloud repatriations are increasingly driven by regulatory reasons, which force organizations to relocate their applications and data. The needle is moving towards enterprise architecture diversity, workload-specific strategy, and well-thought-of hybridization schemes. This is not the end of the cloud era; instead, it is the coming of age of the cloud era.

For most of the tenured technologists reading this, all this will seem familiar because it is.

Technology, just like nature, follows cycles. Our stories began with mainframes, which were those powerful monoliths tightly controlled by IT. Then came client-server, which distributed computing power to a vast network. Cloud came with consolidation in hyperscale data centres, and now hybrid, which is the synthesis of all past patterns. We saw monolithic ERPs rise, rule, and then bite the dust in front of the SaaS ecosystem. Now these very ecosystems themselves are reforming into composable enterprise architectures while AI is banging furiously on the door.

These are not isolated incidents. This is the truth about life, which is that progress is never linear but dialectical. We advance via thesis, antithesis, and finally synthesis. The future is the reconfiguration that integrates the best of what came before. This is a pattern of discovery, adoption, saturation, and correction—just like human thought and civilization.

And it is not just in IT; it is a civilizational phenomenon. Empires rise, expand, peak, fragment, and reform. Philosophies are born in dogma, grow in skepticism, and mature into synthesis. Our own Sanatan Dharma talks endlessly about yugas, which means the time that is not a straight line but eternal cycles where each age leaves teachings for the next.

Cloud repatriation is a reminder that true wisdom is not in novelty but in pattern recognition. And that human judgment should always be more sacrosanct than technological determinism. No S-curve analysis, no algorithms, no hype cycles, and no Gartner quadrants can replace human intuition or strategic foresight. The future lies in seeing both the arc and the loop of history. The real lesson here is not about cloud computing. The real lesson is realizing that the answers we seek may lie behind us, around us, or in the rhythms through which we have already lived. Know when to leap, Know when to return, and Know when to remain grounded. To understand that in technology, as in life, the journey back is the real revolution. And in that return, we rediscover not the past but ourselves.