Indian IT Industry & The dumbing down of an Indian!!

My nephew wants to be like me when he grows up. All those fancy high-tech gadgets, flying around the world, being comparatively richer, and all that pizzazz. How I wish he was not like me!

Who am I? I am a software engineer in the Indian IT industry. Yes, you read it right, a “software engineer,” the folks who are currently perceived in India with the world at their feet and a halo around their heads. It’s not my nephew’s fault, as almost everybody sees the glitz and glamour associated with my profession. I personally see my state and the state of things around me. I see a future, which, to be honest, I don’t like and don’t want to see either.

I grew up admiring intellectuals as well as rich people. So, when the time came to decide what I wanted to be when I grew up, I decided I wanted to be intellectual and wealthy (I&W). During the early nineties, when I got into engineering school, I opted for electronics as my specialization because I heard that it was the toughest (making me an intellectual) and had the best prospects for the future (making me wealthy). Perfect plan!

Oblivious to me, the world was going through what is now called the IT Revolution, and some magicians of the business world were setting up shops, which later would become the hallowed grounds for today’s Indians. However, for me, life couldn’t have been more beautiful. Each time I told new acquaintances that I was studying electronics, they would roll their eyes in awe. The plan was perfect, and I couldn’t have been happier.

However, life presents a mystery that surpasses all others. So, eventually, I found myself out of school and out of a job too.

I believed that I would land a decent job that would fulfil my dreams of being an I&W. But what I realized the hard way was that companies that actually needed electronics design engineers were few and far in between. And the ones that did work in electronics employed folks from premier institutes; I guess with the limited openings that they had, their hunger was satiated with the flock coming from “A” grade institutes or were creme-de-la-creme. I was good, but I didn’t fit in either of the two.

They asked for experience, but there wasn’t any place to work, let alone get experience. The stuff that was taught in college was obsolete. Nobody was asking about it or talking about it. There were very few hands-on design classes. Most of the information was intended to be learned by rote just to get good grades and never used again. The professors that taught these subjects were as old as the books themselves; they had hardened over time to become more dogmatic and closed in their approach. They didn’t learn or explore anything new, and hence they didn’t have anything to pass on to the students, apart from what was in the books and their own pessimistic view of life ahead. Maybe they too had given up, just like I would do in the future.

At that moment in time, however, I didn’t lose hope and continued with my quest for that elusive design or research job. I left my resume with doormen positioned at huge glass entrances of organizations; they wouldn’t even wait for me to turn around before they dumped my CV into the wastepaper basket at their feet. But it was only after months of futile searching, no money in my pocket, and the tremendous pressure to live up to the expectations of friends and family that I realized that my perfect plan was a perfect failure. My focus changed from the “future-perfect job” to the “present-money to survive.”.

It was during this period that a well-wisher of mine told me about the dot-com boom. He told me about how companies were hiring in droves, and that maybe I could get a job. I planned, as usual, that I could take up a software job just to sustain myself and keep looking for that dream opening in research and development (R&D) in the meantime. So, with this intention in mind, I jumped on the IT bandwagon. It's been ten years now.

So, who am I? I am a software engineer. And what do I do? I will dispense that information now.

I am an individual contributor to a software services company. I am one of the faces in the sea of humanity (1.3 million as of 2006) that calls itself the Indian IT industry. If there is any revolution, apart from the Green Revolution (post-independence) and the White Revolution (the 1970s), that has everybody enthralled: the government smiling, the business bosses laughing their way to the bank, and the ordinary Indian jumping with joy in sort of drug-induced ecstasy and shouting “India is shining!” It’s the IT revolution.

If the media frenzy is to be believed, this juggernaut seems so big, so beautiful, so awe-inspiring, so triumphant, and so invincible that somehow, I get this strange feeling of an apocalypse just around the corner. I hope to God that I am wrong, but the current situation does portend it.

You can say that, in this short career of 10 years, I have played (or witnessed) all the rolls that are possible.

- The low-lying software apprentice learns the tricks of the trade (and game) from masters.

- The software developer who has books on software programming on one side and technical specs of the application to be built on the other, coding away to eternity.

- The guy on the phone troubleshooting applications is owned by people who I don’t know and will never know.

- The guy who is sitting here in India sells software on the phone to customers across the world because the English-speaking talent pool is more prevalent here in India and less expensive.

- He is the individual responsible for filing taxes and paying bills on behalf of others, as they lack the time to handle these tasks themselves and prefer to engage in other valuable activities.

- The guy who, as a manager, has hardened and given up (just like the professors he had years ago), who is so addicted to the money and false glory that the only difference between his lie and his life is the “f” in between.

- The guy who keeps repeating to himself that this is the game and that if he stops for lunch, he will become lunch, and hence he starves as he runs with breakneck speed to an ever-recessing finishing line. He shies away from confronting the person he once was.

If you've seen everything, your soul is ready for nirvana. I am confident that my soul is ready for nirvana. But I digress.

By this time, if you are a true Indian or Indophile, I am sure you would be considering me a failure who could not achieve much and is lamenting his life and cursing the environment for his current state. You might think that I am the person who couldn’t stand up to the pressure or gave up when things got tough. And if you are kind-hearted, you might think of me as an unfortunate soul. I might be all these and more. But I would like to bring to light some points.

According to the NASSCOM Strategic Review 2007 report, the Indian IT industry is growing by 28% this year. The total revenue generated from this industry is in the tune of $48 billion, and direct employment is likely to cross $1.6 million. Services and software are the key bread earners in this industry, and NASSCOM estimates that IT services exports, which account for around 60% of the total exports, are growing at an estimated 36 percent and are expected to reach $ 18 billion in 2007. All these statistics sound fantastic and beguile a person into believing that all is well. I am a realist, and I take good news with a pinch of salt.

Numbers are a double-edged sword. If used in one way, they can help in discerning the tree from the woods; the other way around, they can camouflage the tree entirely within the woods. If you don’t believe me, ask the statisticians and CPAs who have been doing this for years. So at times, it’s important to use a healthy mix of statistics with ground realities and other related news. This, I believe, gives a clearer picture of things.

I once heard a joke on IT professionals, which goes like this: What is the similarity between an IT professional and a railway porter? They both ask, “What platform do you work on?” when they meet another of their kind. In a humorous way, there is a very important concept being put across here. And that is stagnation. Every IT engineer worth his salt knows that it’s always beneficial to learn a technology different from the one he is working on. Job openings refer to this as marketability and cross-platform knowledge. In the world of fables, it means don’t put all your eggs in one basket. However, this is exactly what the IT industry is doing; they are putting all their eggs in one basket. I call this the IT Services Vicious Cycle.

IT Services Vicious Cycle: Any self-styled software company looks for money/market share/people utilization, which requires more projects; this puts pressure on the sales/management to find new revenue sources; the sales department under pressure then focuses on low-hanging fruits and easy money; in the current market scenario of outsourcing, services are easy money, and so the sales/management gun for it; with projects comes demand for more people; the organizations hire more people; this increases the bench strength; all businesses look for profit, and it doesn’t make sense to have people on the bench (that’s not profit); hence the pressure on making money, increasing market share, and improving utilization. The cycle repeats itself.

As of now, there are enough services out there that can keep a lot of cash registers ringing and a lot of people on the payroll. The NASSCOM report quoted above proves this. But believe me, things won't remain like this forever. There are new kids on the block who mean serious business and are steadily building the same core competencies that have kept us Indians singing, dancing, and basking in the IT outsourcing sun.

The following are some detrimental effects of the IT Services Vicious Cycle:

The organization is predominantly focused on one thing. This can be because of greed, competition, the battle for market supremacy, etc. It creates the famous rat race, which not only plagues the organization but also permeates its ranks and society as a whole.

This obsession leads to a very narrow outlook towards the market, which basically blinds the organization to other profitable sectors and business initiatives. Other areas where the organization can invest and think creatively in a collective sense are completely diminished or erased.

The race to get better services from professionals leads to the phenomenon of poaching, which is not a good practice. It also makes the individual proud, and he creates a larger-than-life picture of himself. It increases the wage structure, which has a direct effect on the market. This becomes another silent factor in the IT services vicious cycle.

It creates a self-sustaining system where each new employee learns or masters the trade, but more from a service angle. This kills the creativity and innovation inherent in him. He gets into a comfort zone and, after a period of time, resists moving out of it. In extreme cases, he completely banishes the thought of ever moving out of his comfort zone.

I see it all around me. I see folks who complain about the redundant and un-inspiring work that they have been doing but don’t dare move out of it. This is because they are so hooked on it. The job they perform determines their social and financial status. This system is becoming more like a vacuum cleaner that is sucking in talent, and all that you get, on the other hand, is garbage.

Let me explain this: for a new college graduate joining an IT company, he is too insecure and wouldn’t dare but toe the line. He is impressionable and will pick up what is being taught to him or what he sees his colleagues and supervisors doing.

For mid-level and senior professionals, that game is all different. They have a settled life, and the money keeps flowing in. For them, unless they have a brilliant idea that can wean them away, there is nothing that can convince them to not toe the line. It's simply too much of a gamble and too risky to take such a step. Hence, they continue doing what is supposed to be done.

The song and dance sequence about the Indian software industry by the media, the Indian players, and their foreign sympathizers is just a smoke screen to hide the biggest reality of our time. Those companies are pulling in immense talent and making them do low-caliber work, rewarding them with perks and luxuries that they couldn’t have imagined. At the end of the day, we have people who are hooked on a false life and low self-esteem and are burned out and disgruntled. In the industry, employee turnover exceeds 18%. 55%–60% of the time, a person quotes “moving to better opportunities” in the exit interview from his current organization. This “better opportunity” should not be just taken as “better money,” but intrinsically, the person is tired of what he is doing, and that inner urge to do something worthwhile kicks in from time to time. In his illusion that the next company will give him that opportunity, he moves on, finding the same story repeating itself in a different setting. The IT Services Vicious Cycle!!

Professor Sadagopan, a prominent figure in the Indian IT scene, asserts that the inherent nature of software services necessitates a significant focus on skills, particularly those related to software engineering tools. Given that engineers make up the majority of the Indian software workforce, it would be beneficial to utilize their engineering knowledge.

Engineering, by its very nature, is a creative profession (unlike the legal or accounting professions). It can be very satisfying, too. I anticipate that the next phase of the Indian IT industry will focus on software engineering, with the aim of creating remarkable engineering feats.

“The software engineers have an unusually exciting opportunity to move beyond software engineering to engineering software.”

The esteemed professor summed up that innovation, the creation of new product lines, and the development of new technologies provide true satisfaction and profit.

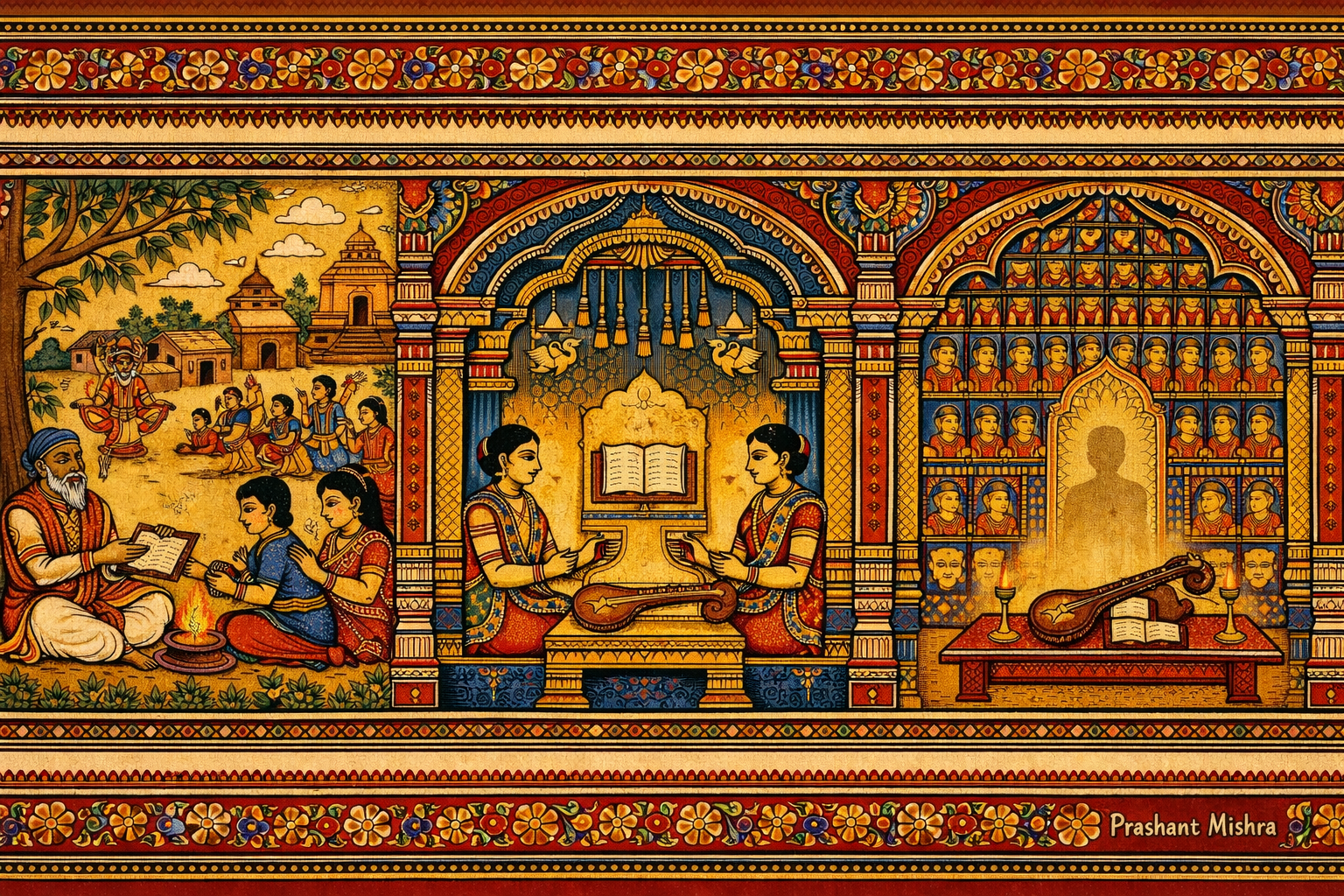

I am paraphrasing some important observations made by Hari Sud, an investment strategy analyst and international relations manager. India has had high intellectual capabilities since the beginning of time. People with low intellectual strengths could not have written the holy texts and sacred books so revered by Indians (the Upanishads and Vedas). The concept of zero traces its origins to India. The science of astronomy was literally born in India, and that couldn’t have been possible without powerful and deep insights into geometry and calculus. Almost 60% of the 64 million college and university graduates hold degrees in science, out of which 9.6 million hold postgraduate degrees.

If intellectualism is considered a power, then India is a powerhouse. But how much of that power are we actually using? According to reports, when the British colonized India, they implemented an education system to ensure the production of high-quality clerks. I am not a doomsday prophet, but isn’t there a similar kind of colonization right now? The only difference is that we're colonizing ourselves. We are reaching out for easy money and low-hanging fruit with scant regard for what the situation could be in the future.

Despite the widespread use of IT today, the creation of computers and the design of micro-chips remain largely a "family affair." In these cases, the family refers to the few organizations that engage in real R&D, primarily located in the west rather than India.

To drive my point home, let me take the case of IT hardware. Arun Shourie, the Union Minister for Disinvestment, Communications, and Information Technology, recently presented some unusual statistics about the IT industry during his speech at the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS). The Indian industry focused 85% of its total output in this sector on serving external customers, whereas China, India's closest rival, focused 85% of its total output internally. According to Mr. Shourie, the performance of Indian hardware is relatively low, indicating a gradual decline in R&D activities, a crucial component of the IT hardware industry.

IT can be a harbinger of prosperity, but if the nation’s entire focus is outwards, then there is little that IT can do. This situation can be really grave in India, where there is an ever-increasing gap between the haves and the have-nots and where the gap in meeting basic needs is enormous.

IT is an amalgamation of three categories: hardware, human, and software. India has already established itself as a software superpower, although the duration remains uncertain. We have attained critical mass in human resources (which means good-quality English-speaking labor) and acute knowledge of software. Based on this, we claim that we have rapid all-round developments in each sphere: the economy is booming, money is coming into the country, ISRO is launching satellites into space, etc. However, this appears to be an unrealistic claim. The state of hardware is awful, and that of R&D is even more tragic. According to research, India can’t even develop high-quality basic components, let alone ICs, chips, and computer processors. This implies that the high-tech capabilities we proudly display rely on components we import from abroad. This implies that our capabilities are all propped up by external agencies, which help us build what we want to build.

Every second person you meet in Bangalore knows C++, Java,.NET, or whatnot. He or she will know some or another software development tool. This is done by rote and by repeated use of the tool and technology. This is because the industry demands it. The industry also bears the financial burden, which is why we frequently read news reports about scientists departing from ISRO and DRDO to join IT MNCs.

It’s a similar case in Pune, Hyderabad, Chennai, and probably Gurgaon. But how many of them can actually create something from scratch rather than just creatively write software? How many can actually create IP? How many individuals possess the necessary environment to generate IP? These are statistics that I would really like to know about.

There are just a few IT organizations (including the one that I work for right now) that are actually making serious attempts at knowledge management and IP creation.

Kiran Karnik (President, NASSCOM) says, “Indians are merely going for software programming; it is like a car mechanic repairing cars, which is a tremendous ability. But while we can repair cars, we cannot design them! We are merely roadside mechanics.” I believe Mr. Karnik is asking us to zoom out of our current hype and obsession and look at the big picture. I believe that he has seen this picture himself, and I guess he isn’t sleeping easy either.

Without adding my own boring drivel, I will quote Mr. Karnik again. “Compare India with China; there is a huge gap. China is today the factory of the world, as it produces 50 percent of the world’s refrigerators and television sets and about 30 percent of the world’s washing machines. India accounts for just 3 percent. Although we have a good share of the services business, in the manufacturing and products business, India needs to go a long way to become a leading player.”

Along with that, China develops its own missiles, which can shoot satellites out of space. I believe the Chinese are bright folks, and I really have great respect for them. In my opinion, they understood the point long before Indians even dreamed about it. They knew that they had to build a solid base in the R&D and manufacturing worlds. They built expertise in science and technology through a focused approach to R&D. Chinese capability in R&D has come to such a level that they can go on their own even without world support. And now that they have that corner covered, there is a strong thrust to make sure that the Chinese population becomes conversant in English, as it’s the de facto language of the world. It's easy to understand why the Chinese are striving to accomplish this.

Unlike India, the Chinese have a strong acumen towards sales and marketing, and they know how to hustle in the world market. The Chinese have the financial muscle to leave India many miles behind. They can pressurize MNCs to set up R&D shops in China in lieu of financial incentives elsewhere. And it’s not only the western MNCs that are recognizing the power of China; if we go by recent events, even Indian giants are in the know. That's why Infosys has established its operations in Beijing!

What is the USP of our IT business? We provide a qualified workforce at lower rates. We can do any kind of work for cheaper rates. IBM was the first company to actually start the software revolution, way back in the 1960s. TCS became the first company to begin the Indian IT software industry by sending Indian labor to the United States in 1974. Software by itself brings together innovation and human knowledge. The real value of software lies in the fact that it can be created and sold (thus making money), but even then, it remains the property of the creator. The software creator can then reap additional benefits by upgrading the software, adding new features, and so on. In contrast, the Indian IT industry does nothing of that sort. The focus is more on doing low-grade work at low rates. There is hardly ever an impetus by the IT giants (barring a few) on Indian soil to ever get into the high-grade, high-paying segment of the IT industry. One of the possible reasons for this could be the lure of immediate profits and the strong desire to maintain sustainability, which by itself is again focused on making more profits.

The high-grade, high-paying work is to develop software products that can be sold to many customers. However, the focus of the Indian industry is not to tap into the immense talent pool this country has to offer to create such products but rather to suck the talent pool in order to help others build their products. This is more like a standardized approach to ensure that the expertise and innovation that are available are used to fill the kitty of an external entity. If the creation of new software products is the real McCoy, then India’s export of labor and services is almost equivalent to low-paying and dead-end masonry work.

The process of developing new branded software requires understanding market needs, interacting with potential end customers, and a heavy dose of creativity. The Indian IT industry entirely depends on the export of cheap Indian labor to onsite locations or the relocation of mundane, repetitive work to off-shore locations. This is the basic business model of every other IT company operating on Indian soil. This work entirely focuses on writing and testing software that has already been analyzed and designed. The customers of such IT companies can maintain constant vigilance over the software being created to ensure the software being developed matches the set ideals. With the advancement of telecommunications and the internet, this is relatively easy. All of this is available at incredibly low costs. It’s similar to designing a Formula 1 car and then asking the highly trained “roadside mechanics” to build it. The mechanics don’t learn anything either from the process because the work entirely involves the fixing of nuts and bolts, performing safety checks, and painting the exteriors of cars based on the specifications provided. In the end, the mechanics are stuck in their dead-end jobs, just making a few dollars, while the creator of the car goes on to mint millions.

The English colonizers used the Indian lands under their control to grow indigo, which was an important component in the cotton clothing industry. This Indigo grown in India was shipped to England and was used to dye the cotton clothes, which were then sold back in Indian markets. Though Indigo cultivation yielded benefits to the British colonizers, a few years of Indigo cultivation would render the subsoil entirely devoid of nutrients, thereby effectively ruining any further cultivation of any kind. In my opinion, this is an alarming parallel between the current Indian IT industry scene and the Indigo cultivation in British India.

The frightening fact is that in the current scenario, it’s not the sub-soil that will be rendered unfit for cultivation but entire generations of well-educated, highly creative, and intellectual Indians. India can somehow tide over the loss of cultivable land but will suffer beyond comprehension due to the loss of cultivable minds. The development of software will probably plateau in the next two to three decades. It’s imperative that the people of today realize this fact and begin looking ahead. Only then can we expect a brighter tomorrow. Until then, the Indian IT industry will continue on its implosive trajectory, fuelled by its own self-professed zeal and lure of money, and the intellectual and creative Indian will continue to be dumbed down into stupidity.