The Subtlety of Nationalism

“The hottest place in Hell is reserved for those who remain neutral in times of great moral conflict”

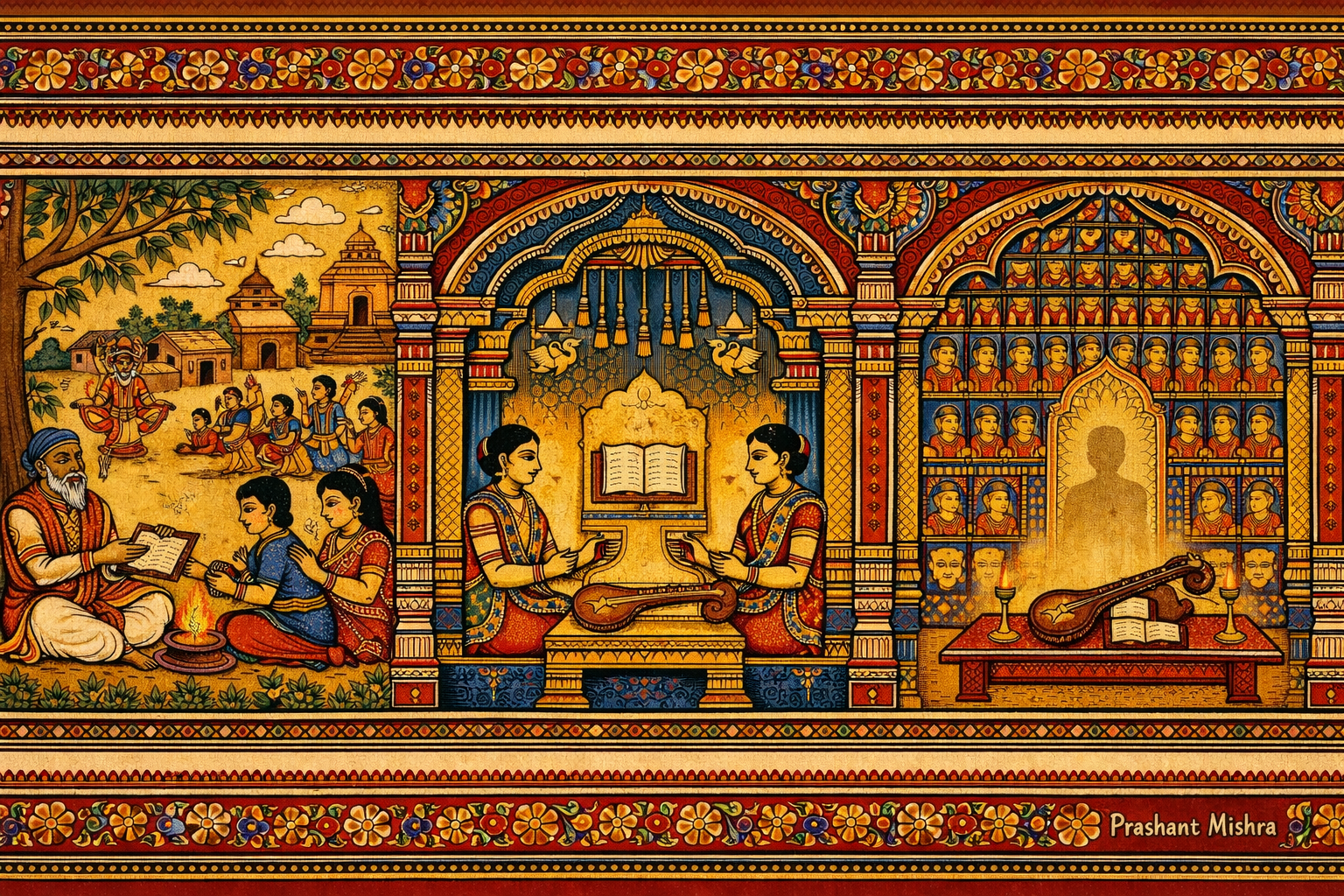

Our rich cultural heritage and fertile intellect have resulted in profound concepts and schools of thought that bring forth wonderful ideas. We love debates, so much so that Amartya Sen coined the phrase “the argumentative Indian” to label the unique tradition that not only appreciates them but also encourages them.

However, arguments can be constructive or destructive, akin to the rapids or meanderings of a river. The rapids shake the system, but they increase flow velocity, allowing new paths to form. Alternatively, they can be languorous meanders that, although flowing, depict a peaceful river that may be unsure of its path. It is these “languorous meanders,” which, although enticing, are the ones that should be treaded most carefully, for they can run deep and drown because of their ambiguity.

The point is that no matter how wise one may be, one always gravitates to describe things, situations, and ideas in terms of “what they are not” instead of “what they are”.

And why does that happen?

It is because intellect finds it easy to describe concepts in terms of what it lacks rather than what it possesses.

In our debate on nationalism, we face a similar “what it is and what it is not” conundrum, and the potential to misdiagnose and cause another series of follies is high.

Its ambiguous definition will resonate globally. For example, in champagne socialite circles, one political party is often portrayed as the silent, suffering custodian of Indian ethos and history. And they have shown some ethereal traits that the current political leadership lacks. Such “soft” values are used to advertise and gloss over the shortcomings of the past. On the other hand, two burly Gujarati men and anyone associated with them are portrayed as graceless, vicious folks dividing all and fomenting hatred. Both untrue.

So, where is the debate on nationalism? Our highly partisan, woke intelligentsia further propagates this confusion. Which, due to “amorphous” values, force us to gravitate towards sides, both of which have lumpen constituents. Such mooring-less discourses become highly viscous. And the very fact that they are happening proves that there is no thought about “nationalism."

Nationalism is defined as “loyalty and devotion to a nation, especially a sense of national consciousness” and "exalting one nation above all others and placing primary emphasis on promotion of its culture and interests as opposed to those of other nations or supranational groups." Patriotism, which is a fuzzier word describing the love for one’s country, the ideals that it stands for, and its history, So, while nationalism is more a ‘with respect to others’, patriotism is a more internal 'self’ concept.

Indians tend to live in ambiguity, terming it “moderation” or "rationalization." We've learned this from a bloody and troubled past. We rationalize our reactions to our situations and circumstances because it allows vagueness to creep in and be accepted as part of the solution. This vagueness provides us with a mechanism to escape uncomfortable questions. And once at a safe distance, utilizing our ingenuity, we apply it to the point that the core ideas become diffused, then proceed to equivocate about them with ourselves and others. This vagueness plays out in any dominant discourse of today.

However, we have been asked sharp questions, so the answers must be too. Examine any era of this subcontinent's history, and you'll discover that instances such as these occur frequently. Whenever we acknowledged or answered them, it allowed us to understand our values and forge ahead. But whenever we avoided them, those uncomfortable questions coalesced into hideous monsters to haunt us.

That same logic applies to our discourse on nationalism. We have been having these self-righteous debates for decades and have gained nothing from them. This indicates that our conversation about nationalism lacks the necessary alignment. Nationalism says that for once we must discard our self-aggrandizing sense of ill-conceived righteousness. There have been multiple wrongs that have happened, and those need to be, at a minimum, recognized and, at a maximum, corrected. Personally, I am tired of my faith, my belief systems, and my way of life being ridiculed, lampooned, and distorted by self-professed ‘intellectuals’, ‘apologists’, and ‘open-minded wokes’. Blatantly false and insulting terms like ‘Saffron Terror’ are hurled to insult, demean, and demonize a faith. I feel burdened and stigmatized just because I am a well-heeled member of a majority religion and a dominant caste. I am constantly reminded of my lineage’s past, as if it were a shame. In all honesty, I would have been happy to bear this cross if I saw others being uplifted, but that is not true either. And so, I am becoming weary of being politically correct for the longest duration ever.

This woke-leftist-liberal sham of self-righteousness and instant-condemnation/apologist/self-doubt of adored idea, person, or thing is false nationalism. It is not a stance that cares about India; it is one that cares about what others think of India—and, by extension, about those who profess it—which is not nationalism. That is narcissism. It is a dangerous manifestation of the need to be the moon for the sun, not the sun itself. It is the self-defeating mind-set of accepting to shine in reflected light, irrespective of whomever the light may belong to.

Hence, the vicious political ideologies. Hence, the never-ending debates. Over decades and centuries, it is these vacuous debates that have allowed our land to be repeatedly conquered, subjugated, brutalized, and brought to its knees by invaders, barbarians, and colonizers. And that is why I argue that our history itself is a bogus story taught to us. History can only be considered history when its view is truthful and 360 degrees. That which we pass off as our history today is just a one-sided narrative, which never really sticks to one side either. Instead, it keeps vacillating, switching to sides that are most convenient.

So, when the nationalism debates happen and we prematurely orgasm to the seductiveness of our own mental contraptions of nationhood and patriotism; reverence to our religion, culture, or past, the questions that echo are “What nationalism?" Which is your nation? Or may I ask, what is your nation? What is the value system that you subscribe to, and is it universal?

We stand at the point where we must truthfully answer these questions.

India is in a state of ferment, and through this catharsis, true national ideas will crystallize. India today is somewhat like the USA during the Great Depression. At that time, America was almost falling apart. With rampant poverty and unemployment, Americans were already thinking of radical changes, including Marxism. There was an inferiority complex and a feeling of futility. However, the passing and hardship of the Great Depression taught the American people the true meaning of economic security and the true value of themselves. It moved them beyond the amorphous ideas of their nation to a more concrete set of traits that defined them and still do. They separated the Church from the State, recognized a Christian majority, and ensured the safety of minorities. They agreed upon irrefutable common rules that were applicable to all, humbly solicited but strongly enforced. Not only that, but they agreed that they would reward industriousness but would not disregard genuine inability. They also agreed that American interests were always the highest priority. These, among others, became the sublime truths of the American concept of nationalism.

Returning to the scene in India, the situation remains dire. This is the proverbial “Samudra Manthan.” The poison will arrive first, before the divine nectar. People will break or bend rules, leading to strife. But let us not rile the already muddied waters and stymie our progress with flights of Aristotelian thinking. We have been doing that for years, and it's yielded little. As Jeremy Bentham stated, the foundation of morals (and legislation) is the greatest good of the greatest number. The author humbly adds that maybe it is true for nationalism as well.

[Explanation of the Quote] In "Inferno,” Dante and his guide Virgil, on their way to Hell, pass by a group of dead souls outside the entrance to Hell. These individuals, when alive, remained neutral at a time of significant moral decision. Virgil explains to Dante that these souls cannot enter either heaven or hell because they did not choose one side or the other. Because they are repugnant to both God and Satan, they are worse than the greatest sinners in Hell, left to mourn their fate as insignificant beings neither hailed nor cursed in life or death, endlessly laboring below Heaven but outside of Hell.

[Image Source] Dennis Jarvis | Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 2.0)